-40%

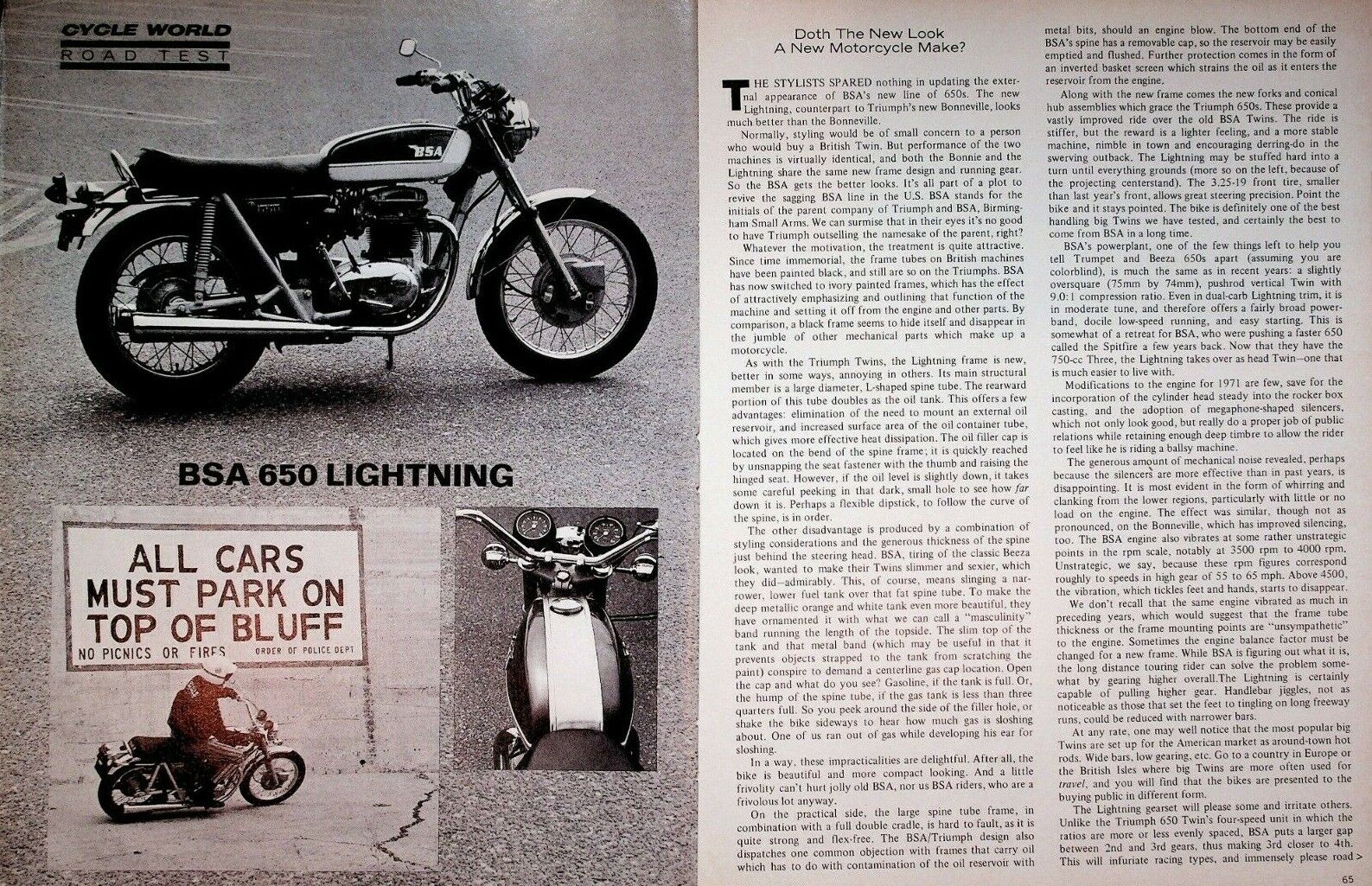

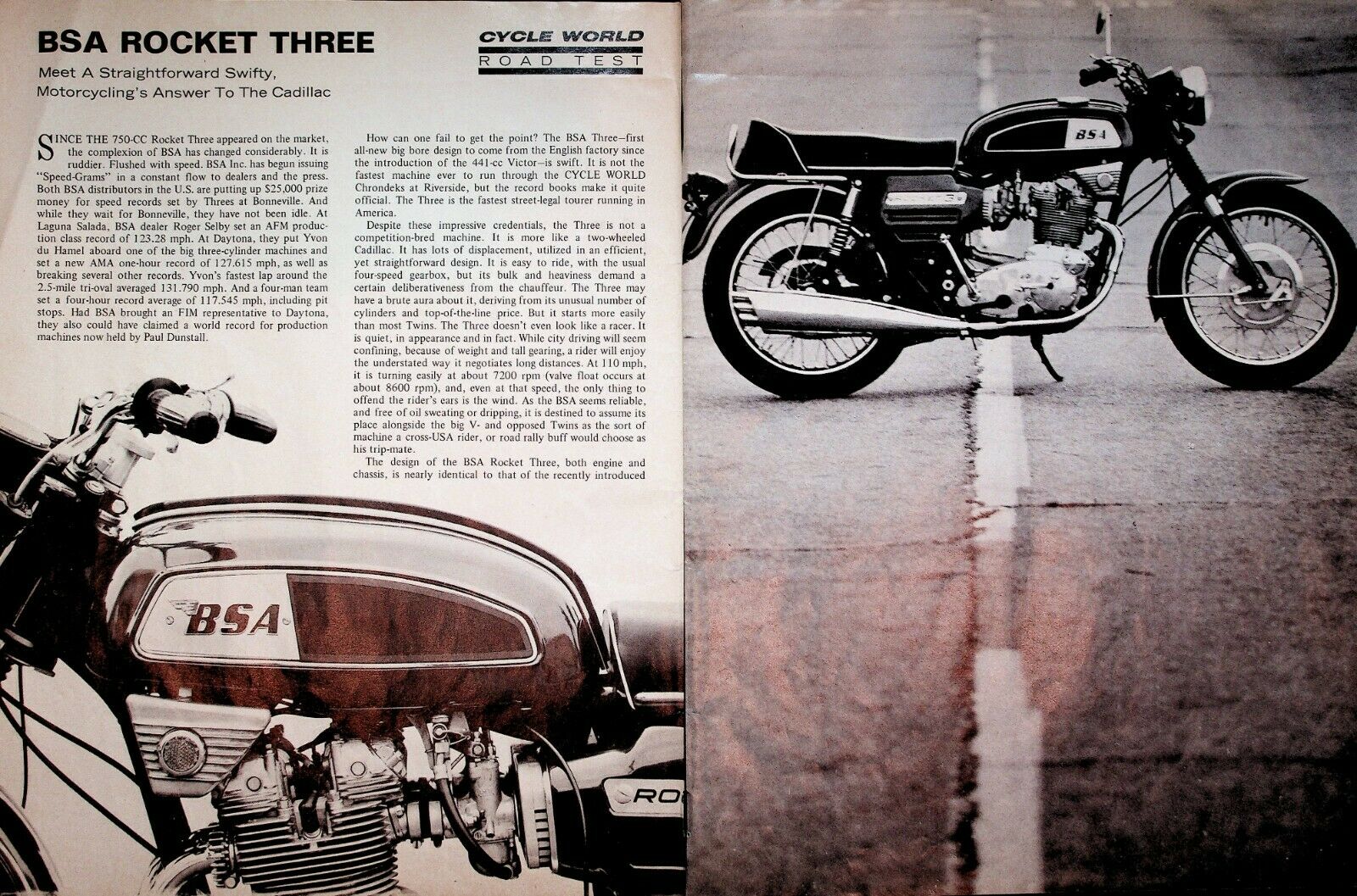

1971 BSA 650 Lightning - 4-Page Vintage Motorcycle Road Test Article

$ 7.89

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

1971 BSA 650 Lightning - 4-Page Vintage Motorcycle Road Test ArticleOriginal, Vintage Magazine article

Page Size: Approx. 8" x 11" (21 cm x 28 cm) each page

Condition: Good

Doth The New Look

A New Motorcycle Make?

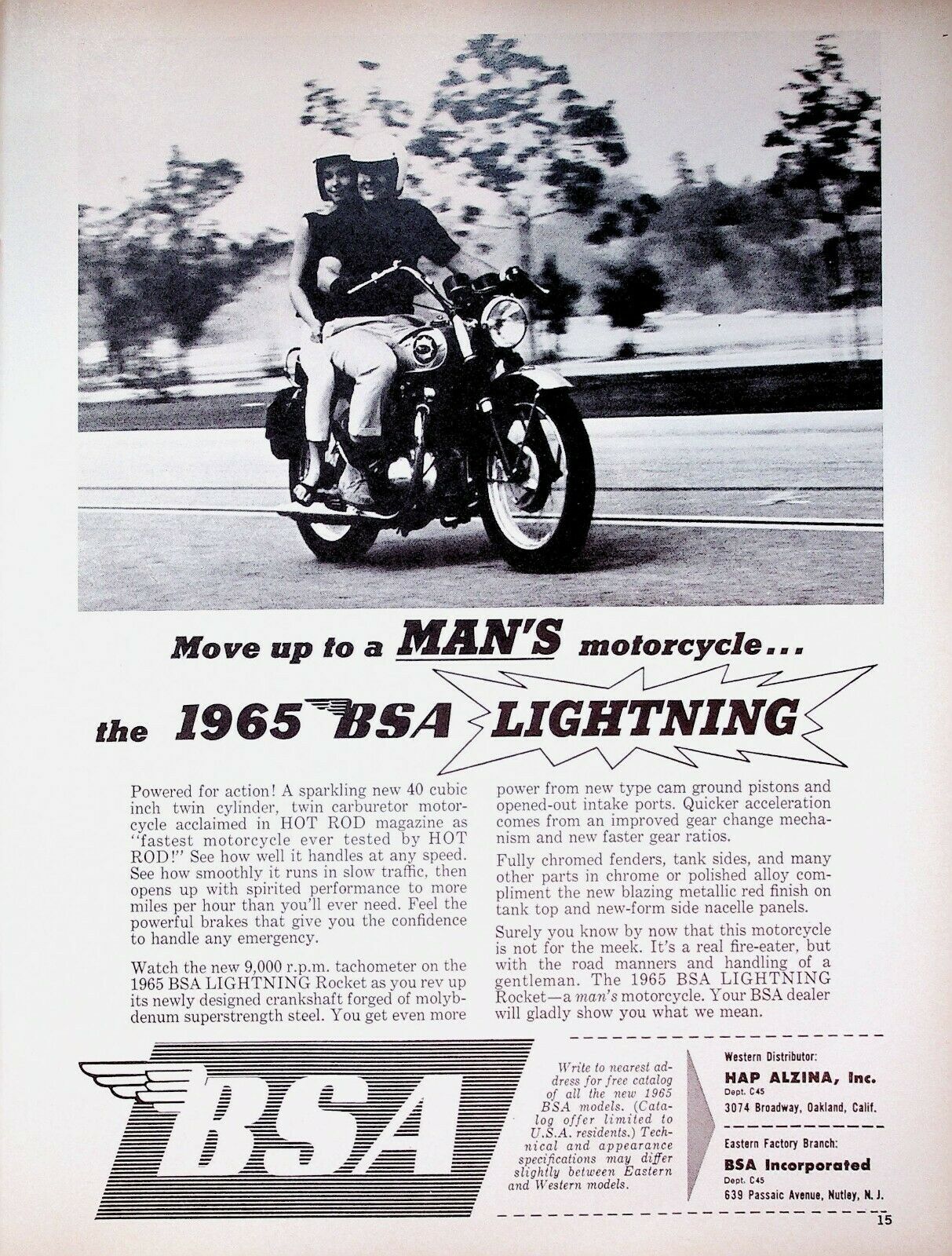

THE STYLISTS SPARED nothing in updating the exter-

nal appearance of BSA’s new line of 650s. The new

Lightning, counterpart to Triumph’s new Bonneville, looks

much better than the Bonneville.

Normally, styling would be of small concern to a person

who would buy a British Twin. But performance of the two

machines is virtually identical, and both the Bonnie and the

Lightning share the same new frame design and running gear.

So the BSA gets the better looks. It’s all part of a plot to

revive the sagging BSA line in the U.S. BSA stands for the

initials of the parent company of Triumph and BSA, Birming-

ham Small Arms. We can surmise that in their eyes it’s no good

to have Triumph outselling the namesake of the parent, right?

Whatever the motivation, the treatment is quite attractive.

Since time immemorial, the frame tubes on British machines

have been painted black, and still are so on the Triumphs. BSA

has now switched to ivory painted frames, which has the effect

of attractively emphasizing and outlining that function of the

machine and setting it off from the engine and other parts. By

comparison, a black frame seems to hide itself and disappear in

the jumble of other mechanical parts which make up a

motorcycle.

As with the Triumph Twins, the Lightning frame is new,

better in some ways, annoying in others. Its main structural

member is a large diameter, L-shaped spine tube. The rearward

portion of this tube doubles as the oil tank. This offers a few

advantages: elimination of the need to mount an external oil

reservoir, and increased surface area of the oil container tube,

which gives more effective heat dissipation. The oil filler cap is

located on the bend of the spine frame; it is quickly reached

by unsnapping the seat fastener with the thumb and raising the

hinged seat. However, if the oil level is slightly down, it takes

some careful peeking in that dark, small hole to see how far

down it is. Perhaps a flexible dipstick, to follow the curve of

the spine, is in order.

The other disadvantage is produced by a combination of

styling considerations and the generous thickness of the spine

just behind the steering head. BSA, tiring of the classic Beeza

look, wanted to make their Twins slimmer and sexier, which

they did-admirably. This, of course, means slinging a nar-

rower, lower fuel tank over that fat spine tube. To make the

deep metallic orange and white tank even more beautitul, they

have ornamented it with what we can call a “masculinity”

band running the length of the topside. The slim top of the

tank and that metal band (which may be useful in that it

prevents objects strapped to the tank from scratching the

paint) conspire to demand a centerline gas cap location. Open

the cap and what do you see? Gasoline, if the lank is full. Or,

the hump of the spine tube, if the gas tank is less than three

quarters full. So you peek around the side of the filler hole, or

shake the bike sideways to hear how much gas is sloshing

about. One of us ran out of gas while developing his ear for

sloshing.

In a way, these impracticalities are delightful. After all, the

bike is beautiful and more compact looking. And a little

frivolity can't hurt jolly old BSA, nor us BSA riders, who are a

frivolous lot anyway.

On the practical side, the large spine tube frame, in

combination with a full double cradle, is hard to fault, as it is

quite strong and flex-free. The BSA/Triumph design also

dispatches one common objection with frames that carry oil

which has to do with contamination of the oil reservoir with

metal bits, should an engine blow. The bottom end of the

BSA’s spine has a removable cap, so the reservoir may be easily

emptied and flushed. Further protection comes in the form of

an inverted basket screen which strains the oil as it enters the

reservoir from the engine.

Along with the new frame comes the new forks and conical

hub assemblies which grace the Triumph 650s. These provide a

vastly improved ride over the old BSA Twins. The ride is

stiffer, but the reward is a lighter feeling, and a more stable

machine, nimble in town and encouraging derring-do in the

swerving outback. The Lightning may be stuffed hard into a

turn until everything grounds (more so on the left, because of

the projecting centerstand). The 3.25-19 front tire, smaller

than last year’s front, allows great steering precision. Point the

bike and it stays pointed. The bike is definitely one of the best

handling big Twins we have tested, and certainly the best to

come from BSA in a long time.

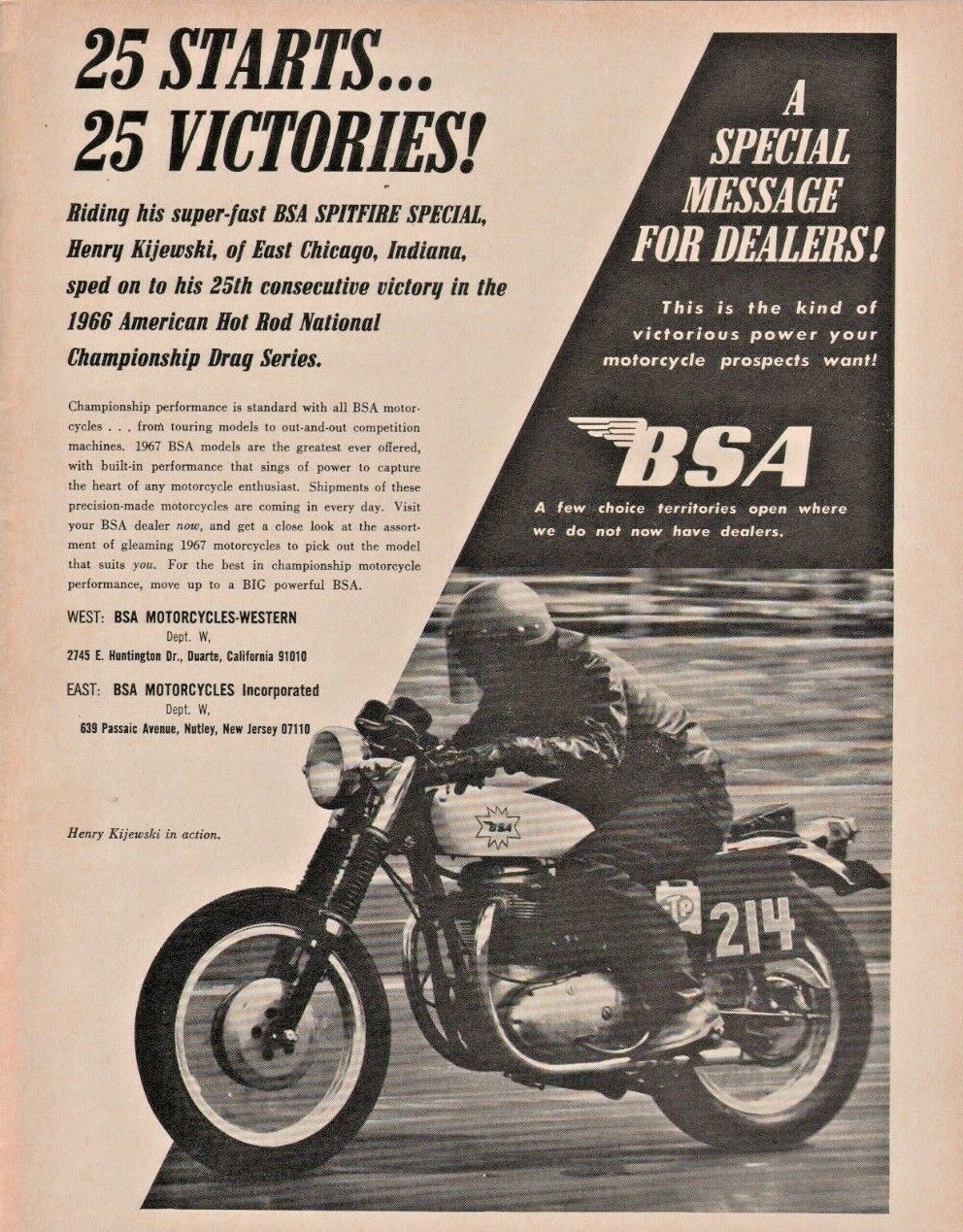

BSA’s powerplant, one of the few things left to help you

tell Trumpet and Beeza 650s apart (assuming you are

colorblind), is much the same as in recent years: a slightly

oversquare (75mm by 74mm), pushrod vertical Twin with

9.0:1 compression ratio. Even in dual-carb Lightning trim, it is

in moderate tune, and therefore offers a fairly broad power-

band, docile low-speed running, and easy starting. This is

somewhat of a retreat for BSA, who were pushing a faster 650

called the Spitfire a few years back. Now that they have the

750-cc Three, the Lightning takes over as head Twin—one that

is much easier to live with.

Modifications to the engine for 1971 are few, save for the

incorporation of the cylinder head steady into the rocker box

casting, and the adoption of megaphone-shaped silencers,

which not only look good, but really do a proper job of public

relations while retaining enough deep timbre to allow the rider

to feel like he is riding a ballsy machine.

The generous amount of mechanical noise revealed, perhaps

because the silencers are more effective than in past years, is

disappointing. It is most evident in the form of whirring and

clanking from the lower regions, particularly with little or no

load on the engine. The effect was similar, though not as

pronounced, on the Bonneville, which has improved silencing,

too. The BSA engine also vibrates at some rather unstrategic

points in the rpm scale, notably at 3500 rpm to 4000 rpm.

Unstrategic, we say, because these rpm figures correspond

roughly to speeds in high gear of 55 to 65 mph. Above 4500.

the vibration, which tickles feet and hands, starts to disappear.

We don’t recall that the same engine vibrated as much in

preceding years, which would suggest that the frame tube

thickness or the frame mounting points are “unsympathetic”

to the engine. Sometimes the engine balance factor must be

changed for a new frame. While BSA is figuring out what it is,

the long distance touring rider can solve the problem some-

what by gearing higher overall.The Lightning is certainly

capable of pulling higher gear. Handlebar jiggles, not as

noticeable as those that set the feet to tingling on long freeway

runs, could be reduced with narrower bars.

At any rate, one may well notice that the most popular big

Twins are set up for the American market as around-town hot

rods. Wide bars, low gearing, etc. Go to a country in Europe or

the British Isles where big Twins are more often used for

travel, and you will find that the bikes are presented to the

buying public in different form.

The Lightning gearset will please some and irritate others.

Unlike the Triumph 650 Twin’s four-speed unit in which the

ratios are more or less evenly spaced, BSA puts a larger gap

between 2nd and 3rd gears, thus making 3rd closer to 4th.

This will infuriate racing types, and immensely please road...

11912-7108-08